Jackie Traverse is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice visualizes the wholeness of her life—joys and sadnesses, desires and fears, relationships and teachings. Traverse was born in Winnipeg and is Ojibwe from Lake St. Martin First Nation. While she’s worked with many mediums throughout her career, Traverse has focused primarily on painting and drawing to tell stories, express feelings, and process events. In this interview, Traverse speaks to how art has helped to support herself, move through grief and pain, and foster connection throughout her life.

Traverse found drawing in a time of loneliness. Her siblings were taken during the Sixties Scoop—a period in which a series of policies were enacted in Canada that enabled child welfare authorities to take or “scoop up” Indigenous children from their families and communities for placement in foster homes, where they would often be adopted by white families. She began to draw in this time of state-imposed solitude, viewing art like a friend and caregiver.

Traverse attributes her foray into creative practices in-part to watching her uncle—who was also an artist—create. Traverse would visit him after he was incarcerated. While he would sometimes tease her about her drawings, it incited her to want to create even more.

Since the age of 18, Traverse had been caught up in the justice system, spending 12 years in and out of corrections. Traverse says there was a 14-year period where she didn’t make art. It wasn’t until she started creating artwork for sale while at Portage Women’s Correctional Centre (Portage for short) that she found her way back to the nurturing, connective practice of creating.

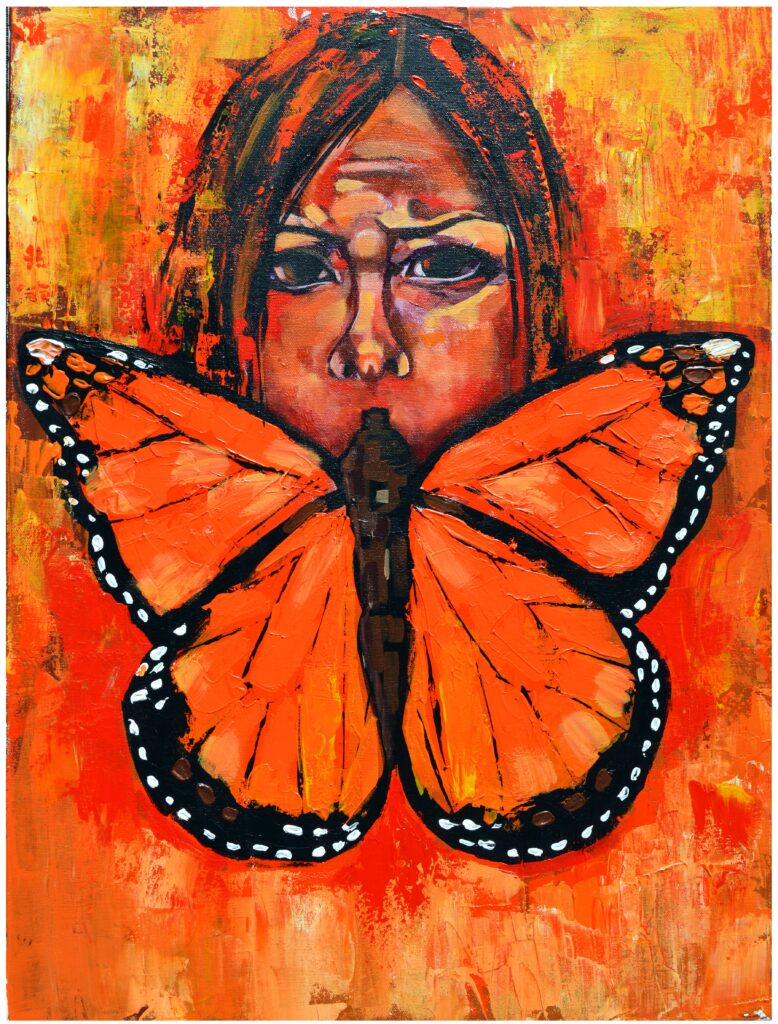

Legend has it if you catch a butterfly and hold it in your hands you can whisper a wish to the butterfly and the butterfly will carry your wish to the Creator and your wish will come true.

Talula Schlegel: Drawing was a form of expression for you through so many stages of your life. I’m curious about what that felt like for you during some of your hardest times.

Jackie Traverse: I remember when I was in Portage, I’d make drawings for people there and sell them for $2 to $5 to pay for my canteen. That was when I first realized that what’s inside me when I’m creating really affects what I’m making. Everyday, they’d have lockdown, they do shift change, so you’re locked in your cells for a couple hours. Usually the doors are open and you can go visit other units and stuff like that. One day, I had some type of issue and was upset, but I had also told this one woman that I would have her drawing ready for her that day because she wanted to send something to her boyfriend. She had already paid me for it and I thought okay, I’m just gonna work on that drawing.

I started drawing and when I was done, I gave it to her and she’s like, “Oh, this looks really angry.” She said, “This is not what I wanted to send to him, like, were you mad when you drew this?” I looked at it and I’m like, yeah, it is kinda ugly. Those feelings of anger and resentment had just kind of poured onto the paper and I never knew that. I was 30-years-old when I realized that what’s inside can transfer to what I’m creating. I realized the power that art had at that time and the effect it had on me. I realized I am a conduit to what I create.

T: Do you feel like in those moments, creating is also kind of a release as well? Even when you don’t know you need to put it out there, it comes out in the way it needs to, kind of like letting something go?

J: Yeah, there was a point in time, probably about eight years ago, my daughter got caught up in a really bad way and I remember how that really affected me because I was powerless to help her. As a mother, especially in Winnipeg, and being the mother of an Indigenous girl, I worried that I would lose my daughter. I was in a very dark place, so I couldn’t work on anything. I couldn’t create anything beautiful. I couldn’t work on commissions, I couldn’t do anything because of how I felt.

But, I would just go to the studio anyway. I would just paint and I felt relief that way. Because of the Sixties Scoop, I don’t have family. I don’t have anybody to turn to to ask for help. So I was really just struggling by myself. I still have those paintings from that period of time. When I look at them, I feel how I felt when I made them. But wow, that canvas and that paint really was there for me when I needed it.

It’s amazing how this flying insect can bring peace and comfort to somebody when they’re hurting.

T: When you think of flight or flying in the imagery that you use, like dragonflies, butterflies, and eagles, are there any teachings or interpretations behind those in terms of healing or processing that you think about while creating your art?

J: Oh, definitely. Especially the dragonflies. There was an elder that was talking about when we leave this world for the spirit world that we journey for four years. And on that path, we’re led there by the dragonflies who are our ancestors. They come in the form of dragonflies and they light the path for us to follow. I make up those scenarios in my mind of how they would look, especially if I was to draw them or paint them. When people speak, I see images and when this elder was talking, I saw the way that path looked and I saw the dragonflies. I’m still chasing that. I haven’t been able to paint that yet, but I keep trying.

I noticed that when I paint dragonflies, a lot of people, especially Indigenous People, they really feel close to that work and they’re quite moved by that work all the time. Out of everything, it’s the dragonfly that really connects people to the artwork. They have the sense that it’s a loved one or an ancestor. I think people are just naturally drawn to the dragonfly. They’re such a beautiful insect because they don’t bother us, hey? They don’t try to bite us or annoy us. They’re just doing their things, serving their purpose, bringing beauty, and when a dragonfly lands on them or comes near them, that’s one of their loved ones coming to say hi to them, or to be with them, you know?

It’s amazing how this flying insect can bring peace and comfort to somebody when they’re hurting. The same with butterflies, it’s just this presence that can bring comfort to people like, how beautiful is that? Butterflies are almost always a tribute to our MMIWGT2S (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Trans, and Two-Spirit People). Legend has it if you catch a butterfly and hold it in your hands you can whisper a wish to the butterfly and the butterfly will carry your wish to the Creator and your wish will come true. My wish is that our women are never forgotten and that they are given the love and respect they deserve.

T: Your short film Butterfly (2007) is a stop motion animation about MMIWGT2S. Why did that medium resonate the best for your message?

J: It sounds so old-fashioned, but I didn’t really have a connection to technology. I’m a person that likes to put my hands on what I’m making. When I was told that there’s this thing called stop motion where you can make the art, make it move, and still get to use your hands, I was blown away. I didn’t realize I could tell stories this way, visually, through moving pictures. After I created Butterfly, I just thought, I’ve been carrying around all these stories like a 3000-pound bag of bricks with me everywhere. It was always right beside me, and it was heavy. Once I told those stories, I was so free, I was so light after I got that out of me.

I was surprised to see, when we would have screenings while putting the video together and they would call me in to tell me what they thought so far, everybody would break down in the room. And I would look around and be like, why are you guys crying? But they said they could feel it—feel the work. It was strong, moving work, and I was like, wow, that’s the power of art, you know?

T: How do you think the art that you make—and art-making in general—can empower others?

J: With some of the work that I do, people have told me things like, “When I saw that painting, I was overcome with emotion, it made me cry” or, “It made me think of my mooshoom (grandpa)” or “it made me think of my dad or my mom, or my auntie, thank you for that.” Sometimes I’m surprised that the work affects people that way, because I’m just working through my own stuff and working from my own heart.

I remember this one artist told me, “You know, Jackie, when you’re in art school, and when you are creating art, if you always work from your heart, you’ll never go wrong. Let your heart lead you. And always if it doesn’t feel right in your heart, then you know, that’s something you have to think of. But if you work from your heart, you’ll always be ready.” That was the first bit of advice that was ever given to me and it still resonates with me today. Lead with the heart.

Talula Schlegel is a musician, visual artist, and writer from Treaty 1 territory, where they currently live.