Stateless in the United Kingdom until age 17, activist and multidisciplinary artist Radha S. Menon immigrated to Regina in 1995 where her acting and singing career abruptly ended and her playwriting career began. Engaging with Menon is truly delightful. Her vivacious personality naturally draws people to her, while her knowledge of arts, culture, politics, and social justice is delivered with a refreshing dose of brutal honesty.

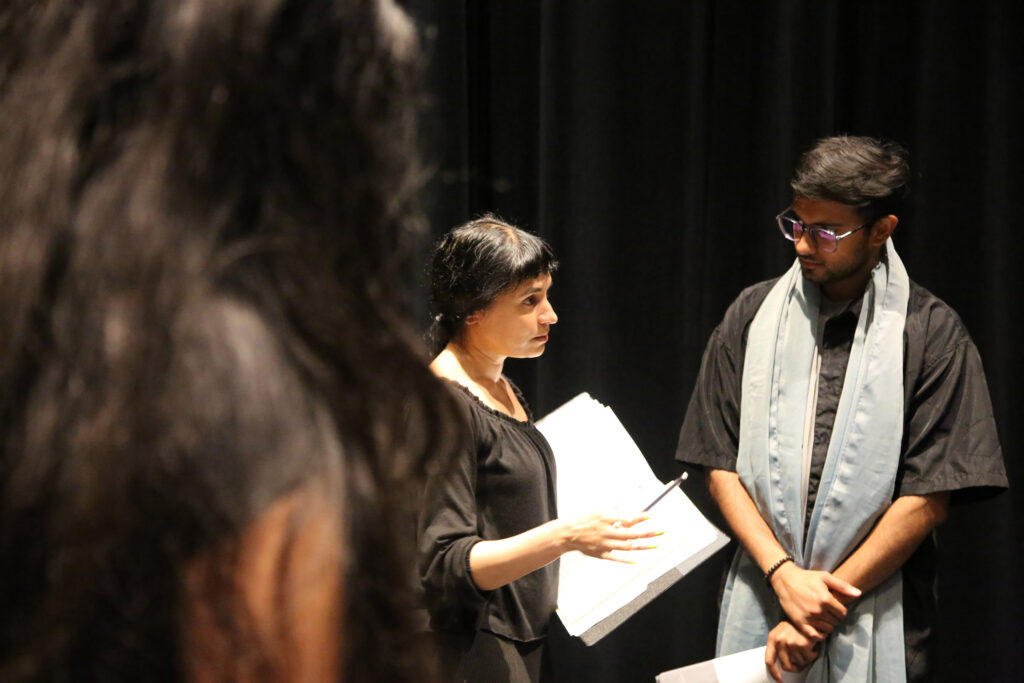

In 2011, Menon founded Red Beti Theatre, Hamilton’s first feminist Indigenous, Black, and people of colour (IBPOC) not-for-profit theatre company. Menon is passionate about the representation of marginalized communities on stage. Her areas of expertise include women’s rights, Dalit rights, and decolonizing theatre.

Each Goddess triumphs in her own way. One could say these plays reflect Radha’s personal triumphs that began when she left home as a teen.

Menon’s plays have been produced at theatre festivals in Canada, the U.S., U.K., and India. They include Blackberry, Ganga’s Ganja, Rukmini’s Gold, Rise of the Prickly Pear, The Circus, The Washing Machine, and most recently, The Devi Triptych, a series that explores the contemporary reimagining of traditional Hindu tales.

Last year, Menon was an artist-in-residence at the Hamilton Arts Council, where she developed her multimedia visual arts project, Touched by Devi, culminating in a solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, June 22 to January 5. Through methods of collage, photography, video, music, and installation, the exhibition included images and narratives of her nuclear family, as well as women who had their high status and practices criminalized and banned by the British, relegating them to the caste of sex worker and Dalit.

Menon’s practice is varied, but her research focus is consistent. Her current artworks and plays are rooted in a 2019 trip to rural Karnataka, India. Menon was on a mission to find women who identify as Devadasi, a girl or young woman who has undergone the Hindu religious practice of being “married” to a deity. That trip and the work that emerged from it are part of an ongoing healing journey as Menon explores the history of women’s rights in India within the context of her own family history.

Menon is putting the final touches on Devi Triptych, three plays each centered on a Hindu Goddess and set in present-day Canada, England, and India. Focusing on Goddesses Sita, Radha, and Renuka, Menon re-examines the classical male versions of these Goddess stories through a feminist lens addressing the challenges, threats, and gender-based violence they experienced in a patriarchal world. This time, however, each Goddess triumphs in her own way. One could say these plays reflect Radha’s personal triumphs that began when she left home as a teen.

Doreen Nicoll: Tell me about your journey to art-making. Why did you decide to travel to Karnataka? What is your connection to the Devadasi (the Sanskrit word for “the servant of Deva/God”)?

Radha S. Menon: I began creating art at a very young age in Cardiff, Wales. My first song arrived with lyrics and melody intact after a deeply traumatic incident of race-driven bullying at the hands of my cherubic classmates as the only non-European in school. Art has saved me, it has kept me alive and I wanted to be a professional artist when I grew up but this idea was shot down.

I was to be a lawyer—due to my big mouth and quick wit—and that was that. No discussion was entertained. I became furious and hopped on a high-speed train to London, ending up in a shelter for unhomed youth. That’s when my poor mother acquiesced.

Many years later, one of my dear aunts showed me photographs of my 14-year-old mother dancing before an audience and told me that Mummy was a thwarted artist. Her father refused to let her train with a professional dance company. I couldn’t understand this aversion to art as a profession.

I began digging and discovered the ancient Devadasi practice where “high-caste” women artists would circumvent matrimonial culture by marrying Goddess Renuka-Yellamma and living in her temple. These artists were powerful and created India’s great classical dance forms. I dug deeper to find that after this great tradition was banned under British rule, it has been degraded to the realm of trafficking young girls from India’s poorest and most vulnerable communities. I needed to know more and set out for Karnataka where there is a strong presence of ex-Devadasi women and the largest Renuka-Yellamma temple. I had never heard of this Goddess before undertaking this research in rural south India.

Art has saved me, it has kept me alive.

D: How did British colonization relegate these revered women to the ranks of coolies (low paid, “unskilled” indentured labourers) and subjugate sex workers?

R: The British criminalized much of Indian culture with sweeping legislation and yanked all power from women, including the practice of Devadasi.

When this practice was outlawed by the colonizers, high-caste women could no longer subvert matrimonial culture and the practice trickled down to “lower” castes. As the tradition faded, it became entrenched in exploited Dalit communities who were offered cash for their young daughters to be sold for sex.

D: To really understand the impact of British colonization on the lives of Devadasi, describe the life of Kariavva, a young Devadasi woman you met who identifies as slave caste and was sold into sex work as a child.

R: Dire poverty and starvation makes people do unspeakable things. These are Kariavva’s words to me: “I remember having seen my grandmother, here and there. I remember her face vaguely even though I was very young. What she did was, when I was 11-years-old, I became a big girl. Do you understand when I say I became a big girl? … As soon as I became a big girl, she tied Yellamma’s beads, she gave me Yellamma’s blessing, and said, ‘It’ll be good to use this girl as a prostitute either at home or elsewhere. Let this girl earn a little money for us. She can give us money, right? She can sell her body to others and fill her stomach and ours.’ She didn’t realize that this could destroy my life. Perhaps she knew. But I feel sad. Why did they do this to me? … I scold my grandmother at times, when I’ve got tension, I scold her, I really scold her, I cry sometimes, other times I grieve.”

Her grandmother’s choice meant sacrificing Kariavva for the sake of the family. This is an age-old tale that goes hand in hand with subjugation and poverty.

D: When you encountered Laxmi, a priestess of Devi Renuka-Yellamma, she performed puja, dancing herself into a trance until she became a vessel for Devi. What happened when Laxmi touched you? How has that changed you?

R: I had just turned off my camera and was putting it away when Laxmi said, “Devi Ma has a message for you. Devi knows that you have been helping her disciples for the past few months and she wants you to know that she is with you always.” Then she placed one calloused hand on top of my head. Light shot down from my crown, piercing all my chakras and water poured from my eyes. “Know this,” she said, “Devi is right behind you. Whatever you do will be successful. Don’t be scared anymore.”

My body trembled in the presence of divinity. I felt warm and safe. All the fear that held me back suddenly vanished. When I left Laxmi’s tiny hut and returned to our car, my assistant asked, “What happened in there? You look different.” I smiled because I was different and still am. I have been touched by Devi and will never be the same again.

I am whole again—not the old traumatized self tenuously held together with toxic glue. I am powerful now. I sit in my power and want to use it to change lives for the better. I can’t do this alone and know that this can only happen when women collectively stop upholding patriarchal norms and reclaim the power of Devi within themselves.

D: When folks bemoan the loss of Hindu culture you ask them, “Whose culture are you really holding on to? Do you really know what your culture is about?” How has colonization impacted Hindu practices and traditions regarding marriage, gender fluidity, fashion, matrilineal lineage, women’s rights, and femicide?

R: I spent three years researching traditional roles of women, especially artists in India before writing Devi Triptych. That’s when I realized that Hindu culture was totally derailed by British colonization. Devi culture was suppressed and Devis pushed into supporting roles for their male counterparts to dominate.

Before the colonization of India, there were eight types of marriage acceptable in Hindu tradition. Only one of them still exists—heterosexual monogamy. Third gender and transgender communities thrived. Today they live in poverty, have little employment, and often must turn to sex work or begging to survive.

Men and women had long hair, wore loose robes over bare breasts. Both wore ornaments, henna designs, and make-up, including eye-liner and lip pigment. Men and women were equally beautified. Then the blouse was introduced by the Brits to wear under the saree because bare breasts were considered obscene. This hypersexualization of a functional organ with a biological task remains. The land that birthed the Kama Sutra has no sex education, but has free porn online, which has increased gender-based violence in India.

Matrilineal and matriarchal communities were the majority all over India. Today, very few remain. Sex wasn’t taboo—it was seen as a way to connect with the Divine. Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples stood on the same shores with churches, mosques, and synagogues in peace for more than a thousand years. Hinduism was all-encompassing, accepting of all, but now India rages with Hindu-fundamentalist views—an oxymoron that is now the norm.

D: How do right-wing Indian leaders use colonial laws and rules to perpetuate misogynistic and patriarchal views limiting women’s participation in the arts, relegating Devadasi to sex work while perpetuating the unattainable female ideal of the original Goddess Sita?

R: Since British legislation curtailed the agency of women in Indian society, high-caste males stepped in the primary position with gusto, pandering to the ruling colonists to their advantage. Consequently women, third gender, and underprivileged classes have suffered and their rights trodden on. Over time, our true culture has been forgotten. Victorian views still linger like petrol fumes ready to ignite communities, as women refuse to accept this bitter fate.

As Tantric Hindu traditions, customs, and practice dwindled, sex became taboo, strictly for procreation and behind closed doors. Women’s sexuality was curtailed through legislation and gods and goddesses who were seen as wanton were relegated to history. Over time, Hindu culture absorbed the Madonna-whore complex that plagues European and Western culture, and the idyllic wife Sita is the prime archetype for Hindu women to aspire to, while sexually liberated Radha is less popular.

Consecutive governments failed to realize that before British occupation, same sex love was accepted and even celebrated as in the case of the Jamali-Kamali’s tomb, which is also known as the gay Taj Mahal. Traditional Hindu myths such as the intense erotic desire between Shiva and Vishnu/Mohini (Vishnu’s female identity) and the birth of their son, Ayyappan, the son of two males, were accepted without qualm.

Traditionally, Indian marriage dowries were paid to the bride’s family. The British changed that to the European mode, and now the female Indian fetus is aborted to avoid dowries of $100,000 plus that became mandatory to marry a daughter. This rabid gender bias has led to a skew in the sex ratio and with 12 million missing girls.

I’m a bit of a shit disturber and decided to join other artists campaigning for parity and change.

D: Pre-colonization people had the ability to improve their caste. What decolonial processes could be implemented to improve the lives of Devadasi as well as Dalits?

R: The first mention of caste appears in the Rigveda written between 1500 and 1000 BCE. This religious text allocates status based on occupational roles. The division of Indian society was based on Hindu God Brahma’s divine manifestation of four groups. Priests were made from his mouth, rulers and warriors from his arms, merchants and traders from his thighs, and workers and peasants from his feet.

Despite this, the Rigveda also clearly states that caste can be altered based on occupation change, that one is not relegated to lifelong restrictions by the caste they are born into. However, during the historical period in India known as the Dominance of the Brahmins, the priestly caste solidified their control by tying karma to caste and halting upward mobility within the caste system. Dark-skinned Indigenous folk were deemed untouchable pariahs and their humanity denied.

When the British took over, they created their own castes while entrenching that hate-filled text, Manusmriti, that codifies the caste system to ensure repression of low-caste folk and women who are seen as casteless. It was this Indo-Aryan philosophy of pure blood that inspired Hitler’s massacre of Jews, Romani, and disabled folk.

D: How has your artistic practice helped decolonize settler Canadian art, theatre, and publishing, while improving access for women, IBPOC, and non-conforming folk?

R: As an artist, throughout my practice, I struggled to find a seat at the table, first in the U.K. and then Canada. It was only when I moved to Hamilton that I could see its blatant systemic exclusion at play. I’m a bit of a shit disturber and decided to join other artists campaigning for parity and change, including co-founding COBRA (the Coalition of Black and Racialized Artists).

In 2011, I founded Red Beti Theatre (RBT) to support my own theatrical practice and quickly realized that Hamilton IBPOC artists and communities desperately needed this space. Well-established Theatre Aquarius was a bastion of white supremacist misogyny that was inaccessible. RBT has grown over the years and now supports other political Indigenous, Black, and racialized women’s voices through our annual Decolonise Your Ears New Play Reading Festival and our more recent initiative, Resilience Residencies, that provide studio space for IBPOC artists to create in a safe and beautiful environment.

My hope is that Red Beti Theatre continues to grow so that it can support, uplift and share the voices of emerging and established Indigenous, Black, and racialized women for many years to come.

Doreen Nicoll is an award-winning journalist and podcaster covering social justice, human rights, and environmental issues. Find her work at doreenn.substack.com.