.

We Were Here, and Have Always Been Here

Black women were here and have always been here, doing all types of intellectual and creative work—writing, reading, speaking, and performing. Black women publishers and editors have been important figures since the mid-19th century in Canada, although their stories are rarely included in the telling of Canadian history. Black women’s history is a collective political and social storytelling project that continues to unfold.

Black women were not working in isolation, or as few and far between as some like to think, but as a conscious group of people who contributed to the critical media of the Black Press—a network of Black thinkers, business owners, publishers, employers, and community advocates. These cultural workers consciously created a transnational space of intellectual exchange, advocacy, and prosperity via the newspaper. This was especially the case in the late 19th to the early 20th-century. However, in the 1940s, mainstream white presses began to actively recruit Black reporters and writers, which greatly weakened the Black Press.

The Black abolitionist movement was a key part of the network’s philosophy and labour. These Black revolutionaries risked their lives as free and self-emancipated people who actively and openly opposed slavery in a social and political environment where kidnappings and murders were everyday concerns. By the mid-1800s, they had fought against slavery in the Americas, focusing on African Americans. The early emancipation proclamation by the British Empire in 1834, triggered by the Haitian Revolution (or, la Guerre d’Indépendance, as Haitians know it) further encouraged the use of freedom routes, known as the Underground Railroad, through which Indigenous, Black, and white abolitionists guided freedom seekers to Canada. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) shook the whole Western hemisphere. This struggle for liberation left an imprint of what freedom could look like in minds across the world.

In the Freeman, Shadd published on women’s rights, abolition, temperance, and the suffrage movement, seeking to shift her community’s perspectives about freedoms women were denied.

Setting the blueprint for abolitionist feminist writing

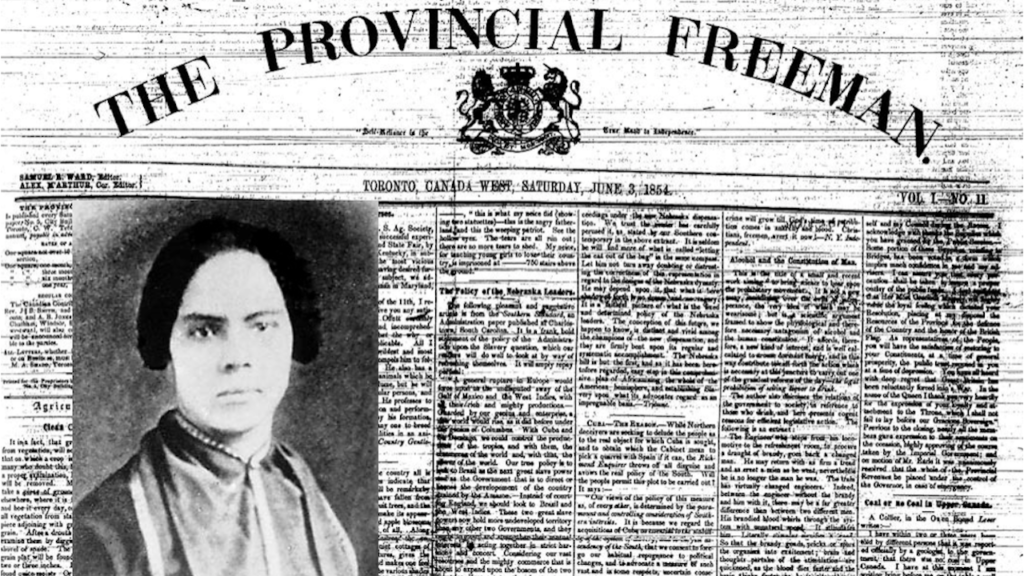

Among the abolitionist revolutionaries who left their mark on Canadian history was Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893). Known as the first woman publisher to independently create a newspaper in North America, she was designated as a national historic person in Canada in 1994. Shadd Cary left behind a legacy that cannot be understated. She was born in Wilmington, Delaware in a community of free Black people. She moved to Canada West (present-day Ontario) to flee the threat of enslavement after the passing of the United States’ second Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This act allowed enslavers to enter free states to kidnap previously free and self-emancipated Black people alike. In order to voice her own opinions, which differed from peers like Mary Bibb and Henry Bibb—a couple who published the Voice of the Fugitive until 1854—Shadd established the Provincial Freeman (1853-1857).

The Freeman was first published in Sandwich, Ontario (currently a neighbourhood of Windsor). Unveiled in 2022, a statue of Shadd Cary now stands in the City of Windsor to recognize her contributions. Shadd moved her newspaper from Sandwich to Toronto after only two years, where a plaque was established in her name in 2011, to inscribe her in our memories. Finally, the Freeman settled in Chatham, which was home to a critical hub of Black entrepreneurs and committees that dealt with politics, business, and vigilance from the 1850s and well into the early 1900s. In 2009, a bronze bust of Shadd Cary was erected at the BME Freedom Park in Chatham-Kent in memory of her work.

Many women publishers’ and editors’ work behind the scenes has gone undocumented and uncelebrated. This is what historian Afua Cooper reminds us about Black educator and editor, Mary Bibb. In her essay published in the anthology, We’re Rooted Here and They Can’t Pull Us Up (1994), Cooper explains that because Bibb was well-educated, a teacher, and expressed strong political views in favour of Black education, she is believed to have been the co-editor of Canada’s first Black newspaper, The Voice of the Fugitive (1851-1854), alongside her husband.

Too often, Black women’s histories are told with a pinch of hesitation, as though there is doubt that it is possible for Black women—of all women—to have accomplished such endeavours. In actuality, Black women had more freedom and range because we had historically been left out of the ideals defining womanhood and respectability. These narratives have controlled and surveyed women’s lives across time and place. Social and gendered parameters undoubtedly affected Black women, especially of a certain status, but they were designed in the Victorian patriarchal ideology as a way to control white women’s lives through a puritanical iteration of womanhood. These ideologies simultaneously upheld Western racial hierarchies. Black women’s experiences and their sense of womanhood were unconsidered.

In her book, Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century (1998), United States historian Jane Rhodes confirms that Shadd launched her own newspaper using the name of Samuel Ringgold Ward, her co-editor—a minister and friend who was often travelling and away—to launch her mastermind project without the general public’s suspicion that a woman was behind these operations. In the Freeman, Shadd published on women’s rights, abolition, temperance, and the suffrage movement, seeking to shift her community’s perspectives about freedoms women were denied. Shadd also heavily criticized white abolitionists for the despise they expressed towards Black people, treating them as though they had nothing and should be grateful for poor quality books and clothing.

Black women, then and now, commonly embodied this philosophy of uplifting one another and their community, to “uplift the race.”

In her pamphlet, A Plea for Emigration, or Notes of Canada West (1852), which argued in favour of African American migration to Canada, Shadd criticized the practice of donating goods that maintained people in the position of “beggars,” rather than uplifting them to act as autonomous and capable people. Black women, then and now, commonly embodied this philosophy of uplifting one another and their community, to “uplift the race.” One way this camaraderie was accomplished was through publishing mentorships and opportunities.

A community endeavour

Writing and publishing became a family undertaking, with Shadd drawing her younger siblings into the work. Her sister Amelia Shadd covered for her when she went away on lecture tours. Her brother, Isaac Shadd, continued to run the newspaper with H. Ford Douglass and the help of Shadd Cary’s husband, Thomas Cary—whom she married in 1856. The newspaper ended in 1857, when Shadd Cary gave birth to her daughter, Sarah Elizabeth Cary. Shadd Cary was committed to documenting Black histories of revolt and liberation. She challenged gender norms and drew women into publishing and editorial work. Shadd Cary’s later publication projects included documenting political opposition and revolts against slavery that took place in the United States.

It was in her blood. Shadd was the daughter of Abraham Shadd, who was involved in Black liberation efforts and politics, and Harriett Parnell, whose life is less documented. The Shadd lineage was made up of business entrepreneurs and free Black people. Prior to running her newspaper, Shadd was a school teacher at the integrated school she had established to promote Black education. This went against the views of other Black settlers in Canada West (present-day Ontario)—like the Bibbs, who favoured segregation as a way of creating safer learning environments—and it defied white people’s racist desires to stay separate in the 1850s in Canada West .

Before settling in Canada, Shadd’s A Plea for Emigration informed African Americans about the privileges and “promise” of freedom in Canada West, hoping to encourage freedom seekers to flee further north. Although Black people were not as welcomed as abolitionist propaganda suggested they would be, the ideas of promoting Canada as a safe haven were part of a tactic to discredit and weaken slavery in the United States.

From anti-slavery organizing to radical press activities, Black women like Shadd Cary were involved in women’s rights and civil rights struggles, including the women’s suffrage movement.

From anti-slavery organizing to radical press activities, Black women like Shadd Cary were involved in women’s rights and civil rights struggles, including the women’s suffrage movement. While Black people, as British subjects, technically had the right to vote following emancipation, poll taxes, racist sentiments preventing them from attending polling stations, and the requirement to own property were salient barriers to their material enfranchisement. Black women were further limited by gender. According to Canadian historian Natasha Henry’s 2018 article in Heritage Matters, “[Black women] had to be able to prove their citizenship status as British subjects and later Canadian citizens, born or naturalized and they had to own taxable property of a certain value.” Although Shadd Cary acquired her naturalization papers and passport by 1865, most Black women would not have had these documents.

Shadd Cary eventually returned to the United States to help rebuild the American South after the Civil War in 1863 during the Reconstruction period, where her papers offered her added security to travel.

A legacy of feminist killjoys

Shadd Cary left a mark in Ontario by breaking “the editorial ice,” as Rhodes writes. She was a feminist killjoy who refused the status quo on so many levels. Coined by U.K.-based author Sara Ahmed, a feminist killjoy is someone who bursts bubbles and brings the uncomfortable truths to the table. Shadd Cary was part of Black feminist legacies of disruption and histories refusing to be forgotten. These legacies are a strong reference point for later generations of Black women writers, journalists, and intellectuals. Shadd Cary shamelessly challenged her Black contemporaries’ blatant sexism and white abolitionists’ ‘benevolent’ racism. As Ahmed states in the fall 2023 issue of Herizons, “The feminist killjoy is [and has] a history.” Publisher and advocate Shadd Cary embodied that.

Further east, yet still connected to these conversations and to a commitment to Black consciousness in Canada was another fierce woman publisher, Miriam A. DeCosta. She co-founded The Atlantic Advocate in Halifax with her husband, Wilfred A. DeCosta, and their friend Clement Courtenay Ligoure. Published between 1915 and 1917, it was Nova Scotia’s first African Canadian news magazine and there are only four surviving copies left. The Advocate, a Pan-African newspaper, discussed political, social, cultural, religious, economic, and literary topics. It promoted and celebrated Black women writers who recorded Black history with urgency, who were concerned about the scarce and disconnected pieces of information on Black people’s lives and wanted to preserve this important collective memory.

“We are today longing for better conditions; we must put in operation forces which, if accompanied by the right personal activity, would speedily bring the fullest realization of our fondest dreams.

As a co-editor, co-publisher, writer, and secretary for The Advocate, Miriam A. DeCosta was influential in the curation of text, the direction and planning of the newspaper, and the larger conversations burgeoning from those intellectual spaces. Although DeCosta was constrained to writing on certain topics based on gendered expectations—including pieces on morality—her surviving texts and her role within the industry offers a glimpse into her thoughts and life.

In her article, “The Road to Prosperity,” she speaks of her aspirations for the Black community: “We are today longing for better conditions; we must put in operation forces which, if accompanied by the right personal activity, would speedily bring the fullest realization of our fondest dreams. […] When we come into higher realization and bring our lives into complete harmony with the higher laws, we will then be great enough to attract success. We can then establish in ourselves a strong centre.” Like Shadd Cary, her involvement opened the door for other Black women writers to express themselves and leave their mark. DeCosta had surely known about Shadd Cary, who was part of the generation of writers preceding hers, however, Shadd Cary would have passed away before DeCosta settled into her career.

Recuperating Black women’s stories is a matter of recounting a more layered history that pushes against erasure and misinformation. Shadd Cary and DeCosta remind me of the urgent gaps in collective memory, the desires for social change, and the impactful ways of addressing social issues by using a historical perspective to get to the root of them. Our present reality is shaped by legacies of the past that, even when unrecognized, still dictate our making of the present and the future. So, this is for Black girls and Black women who need a reminder that indeed, we were here, and have always been here; through historiography, we hold the future.

Emilie Jabouin is a researcher, dance artist, and founder of DO GWE dance & research, interested in Black women’s histories, archives, performance, and liberation. She has a PhD in communication studies from Toronto Metropolitan and York Universities. https://www.emirj.ca/