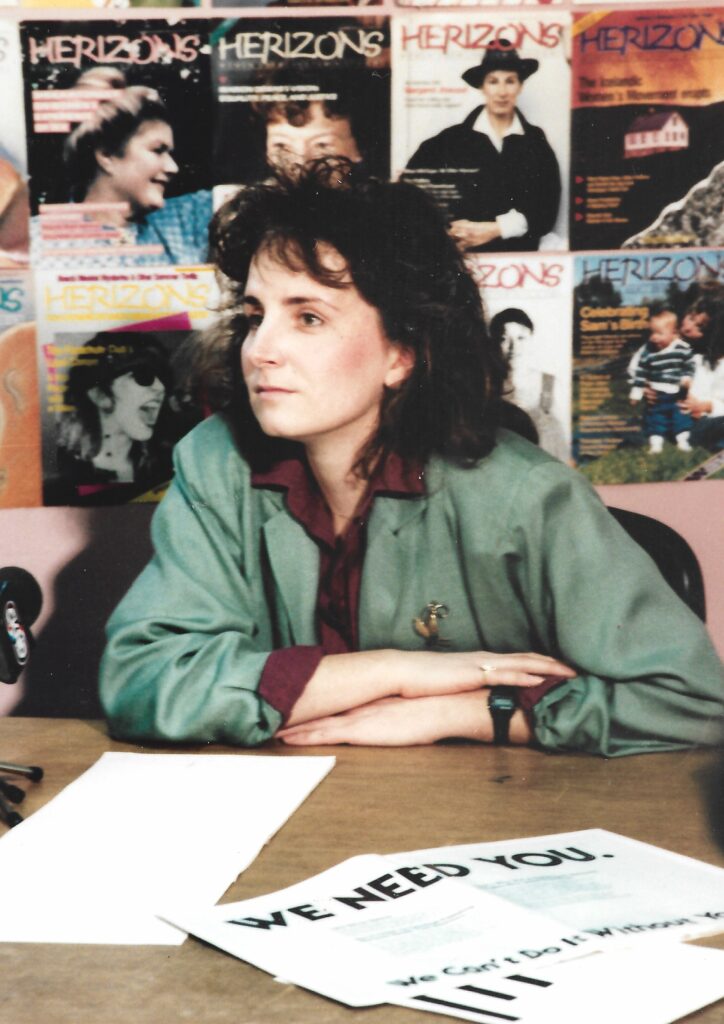

For Penni Mitchell, there wasn’t much question about what she wanted to do with her life. It was clear from the moment she heard about a feminist protest taking place in Winnipeg. Mitchell was co-editor of the Red River College student newspaper in 1980.

“They were talking about a sexist window display and how they were all going to hold a protest and some of them wanted to throw bricks,” Mitchell said. “And I thought, those are my people!”

Soon after completing her journalism studies program, she began volunteering for Winnipeg’s new feminist publication, The Manitoba Women’s Newspaper, and working as a freelance writer. In the fall of 1982, Mitchell, 23, landed her “dream job” as a co-editor at the newspaper. A year later, the newspaper, by then called Herizons, would transition into a magazine.

It was an exciting time for social activism, and the feminist movement wasn’t any different. The United Nations had declared the UN Decade for Women (1975 to 1985), signalling rising global consciousness about how women worldwide were being systemically discriminated against. In Canada, the Royal Commission on the Status of Women—established in 1967 after years of lobbying by feminists nationwide—held hearings across the country and published its groundbreaking report in 1970. This led to the formation a year later of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (1971-2007), an umbrella group of feminist organizations whose mandate was to lobby governments to implement the recommendations of the Royal Commission.

All across Canada, collectives of feminists were putting out films, videos, and radio programs, as well as print media such as newsletters, newspapers, magazines, and books. There were some 900 such feminist initiatives between the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, according to Analogue Revolution: How Feminist Media Changed the World, a Canadian documentary released in 2023. These enterprises typically ran on a shoestring budget, heavily reliant on volunteer labour. Many folded after a few years, never to rise again.

Herizons was different.

Founded in 1979 as a feminist collective with Deborah Schwartz (then Holmberg-Schwartz) as its coordinator, Herizons lived two lives. The first incarnation began in 1982 when Schwartz applied for and received a startup grant from the federal government under the Local Employment Assistance Development program. The money allowed Herizons to hire a staff of six—most of whom were previous volunteers. They rented an office above a Mexican restaurant in what was then Winnipeg’s hippest neighbourhood—Osborne Village. Publishing 10 times a year, the format quickly changed from a newspaper to a more visually appealing magazine.

It was a high-energy working environment. Mitchell recalls that managing editor Schwartz was the centre of gravity around which lively discussions about feminism swirled. To Mitchell, Schwartz was a mentor. “She viewed feminism as a human endeavour being carried into existence by women,” said Mitchell. “It wasn’t a fight, which is more how I viewed it. Her approach was always to bring people in, to listen to them. She was—and is—a gifted leader.”

Unlike most workplaces at the time, Herizons was child-friendly, and therefore sometimes chaotic. Kids would do things like hide in gigantic canvas mailbags. Patricia Rawson, Herizons then-financial manager and a single mother of two, recalls how “the children were an integral part of the work scene, sometimes attending editorial meetings with their mothers and helping with mail-outs.” Schwartz and Mitchell both gave birth in 1983 and often brought their children to the office.

Those were heady days. For a time, author Carol Shields was Herizons’ fiction editor. Because of its pro-choice stance, Herizons was the target of anti-abortionists, including the local archdiocese, and Herizons was frequently in the news. By 1985, Herizons had as many subscribers from outside Manitoba as within the province. “So we decided it was okay to start calling ourselves a national magazine,” Mitchell said. National attention brought greater recognition and in 1985, when Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was published, Herizons co-hosted a reading by the famed Canadian author at a small local bistro.

Re-imagining endings as beginnings

By 1986, circulation peaked at around 7,000. Still, the revenue was not enough to sustain the magazine, especially once its federal funding came to a halt two years after Brian Mulroney’s Conservatives came to power with new funding priorities. Herizons ceased publication in early 1987.

For the magazine’s readers and its staff, it was the end of an era. Some, including Herizons’ managing editor Schwartz, announced plans to move. “I needed to step away. I was exhausted from overextending myself as a mother of four children under the age of 10,” said Schwartz. “But I also had a sense that it could be re-imagined under new leadership.”

“I was just devastated, I could not believe it,” added Mitchell. “I think I just stewed about it for five years.”

Mitchell found a job with the Manitoba Women’s Directorate—a government body that later merged with the Women’s Advisory Council to form what is now known as Women and Gender Equity Manitoba—that included writing speeches for NDP Status of Women Minister, Judy Wasylycia-Leis. When the NDP government fell to the Progressive Conservatives in 1988, Mitchell was reduced to writing fire safety brochures and similarly mind-numbing literature. The five years spent in bureaucratic purgatory were a far cry from the cutting-edge feminist publishing she loved.

It was during this time that Mitchell became involved with the Manitoba Coalition for Reproductive Choice, where she met other feminist writer-activists who would later join a group of a dozen volunteers to assist with Herizons’ relaunch.

Gone were the labourious processes of manually cutting and pasting articles and photographs with X-acto knives and typewriting manuscripts.

Mitchell could see a route emerging through advances in computer technology, especially desktop publishing. In the five years between 1987 and 1992, technology “went from [practically] nothing to where you could essentially publish a magazine on a computer.”

Gone were the labourious processes of manually cutting and pasting articles and photographs with X-acto knives and typewriting manuscripts. In came floppy disks and email. The endeavour no longer called for half a dozen employees. Now, two people could do most of the work from home.

Home for Mitchell was a century-old house in Wolseley, nestled in Winnipeg’s granola belt. She continues to live in the neighbourhood, and visiting grandchildren live nearby. As luck would have it, Rawson, Herizons former financial manager, lived down the street and also wanted to revive Herizons. “I liked the idea, and still felt committed to the magazine,” said Rawson. A group of about ten volunteers were also keen to help.”

After being pushed out of her job due to government austerity measures, Mitchell used her severance to buy the best computer she could find. Together with Rawson, they began work on a new iteration of Herizons. Schwartz, who had moved to B.C., recalls feeling “thrilled” upon hearing the news.

The team’s first task was to contact Herizons’ old subscribers, whose names and addresses were stored on recipe cards in shoeboxes. Family members were recruited to type thousands of names onto floppy disks. Mitchell contacted hundreds of women’s organizations and asked them to distribute subscription forms to their members.

Our goal was to get 3,000 subscribers or we would send their money back. And we did it.

“It was very old-fashioned, but it worked,” Mitchell said. “Our goal was to get 3,000 subscribers or we would send their money back. And we did it.”

The first issue of the new Herizons came out in March 1992 and it has continued to publish on a quarterly basis ever since.

The topics covered changed over the years. Issues of Herizons published in the 1980s carried many articles on the pro-choice movement, which culminated in the landmark Supreme Court of Canada ruling in 1988 that declared Canada’s abortion law unconstitutional. The early Herizons also documented the struggles of affordable daycare, ending discrimination in divorce laws, and improved maternity leave—advancements we may take for granted today.

Other issues were slow to reach attention, like sexual harassment. “It was difficult to cover. People weren’t coming forward,” Mitchell said, “because that meant identifying yourself.”

Among the few to go public was Bonnie Robichaud. In 1980, she filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission, saying she was pressured into a sexual relationship by her supervisor while working as a cleaner at a military base. In 1987, Robichaud won her legal battle against the Department of National Defence. Despite the landmark ruling, most victims of harassment remained powerless and isolated for decades.

“And then MeToo happened,” Mitchell added. “Wow, what a sea change when women mobilized online!”

Another sea change within the feminist movement—and Herizons—has been a more intersectional lens on social justice. “I feel that from the get-go in 1992, we did make a concerted effort to ensure voices of women of colour were at the forefront in Herizons.”

In the new incarnation, columnists even included Rosemary Brown, the first Black woman to sit in a provincial legislature and the first woman to run for the leadership of a major federal political party. “That felt like a bit of a coup. And Jeannette Armstrong, an Indigenous writer and educator, was Herizons’ first Indigenous columnist.”

Keeping Herizons alive

When asked what she is most proud of, Mitchell reflects for a moment. “Having solid writers who kept the magazine relevant, and really dedicated readers who supported it feels like a huge accomplishment when other feminist magazines went by the wayside.”

Some of the fallen publications include: Vancouver’s Kinesis (1974-2001), Thunder Bay’s Northern Woman Journal (1973-1995), Toronto’s Broadside: A Feminist Review (1979-1989), Quebec’s La Vie en Rose (1980-1987), Halifax’s Pandora (1985-1994), and Toronto’s Tiger Lily: A Journal by Women of Colour (1986-1993).

Herizons nearly met the same fate. Advertising, subscriptions, donations, and project grants sometimes fell short of paying the bills. More than once, Herizons was on the verge of shutting down when “the goddess of feminism dropped some money on us,” Mitchell said with a smile. On a few occasions, it was a sizeable drop from friends of Herizons that kept the doors open.

“One time, we were in a really tight crunch, and a woman in Thunder Bay, Margaret Phillips, got in touch. She ran the last existing feminist bookstore in Canada, Northern Women’s Bookstore,” recalled Mitchell. A friend of Phillips who passed away had asked her to distribute some estate funds to feminist causes. “She sent Herizons a large donation out of the blue. And it was like, hallelujah! We were just a second or two away from closing.”

Phillips, who passed away in 2015, had the kind of dedication typical of many of Herizons readers. To this day, 20 percent of the magazine’s subscribers make automatic monthly donations to help keep it afloat.

Some give money, others give their time and ideas. “Herizons wouldn’t have survived the last 20 years without the work of Ghislaine Alleyne, Kemlin Nembhard, Gio Guzzi, and Valerie Regehr,” Mitchell said about the community members that make up Herizons’ board and editorial advisory committee.

To Mitchell, the job of an editor is to help bring the writers’ ideas into clear focus. Cheryl Thompson, in her final column on racism and culture in Herizons’ spring 2023 issue, gave a shout out to Mitchell’s editing skills. “One of my most read pieces, ‘The Sweet Taste of Lemonade’ [2016] … was initially rejected,” she wrote. ”I submitted a draft to Penni that was biting. I criticized Beyoncé’s brand of feminism and her celebrity following…. Because of Penni’s thoughtful critique, I revised the article, and today I’m incredibly proud of the version that was published!”

Schwartz believes Mitchell succeeded in keeping Herizons alive because she had the “tenacity and fire” required for the job.

Schwartz believes Mitchell succeeded in keeping Herizons alive because she had the “tenacity and fire” required for the job.

In addition to managing the magazine, Mitchell was a regular Winnipeg Free Press columnist from 1995 to 2007, and in 2015 she wrote a primer on the history of women’s rights, About Canada: Women’s Rights, published by Fernwood Publishing. Today, her daughter Kaitlyn Mitchell is director of legal advocacy at Animal Justice, an organization that recently sued the Ontario government over its laws prohibiting whistleblowing about farm animal cruelty. Clearly, working to make the world a better place runs in the family.

Since July 2022, when Herizons hired senior editor Christina Hajjar, Mitchell focused on circulation and fundraising while supporting Hajjar’s transition into a full-time managing editor role. In April of this year, she retired.

“Penni demonstrated over and over her dedication to the magazine through stretching her skills, and working long hours to make it happen,” said Rawson, who spent two years with the new Herizons as business manager before moving to the West Coast to fulfill a lifelong dream.

“She was steadfast in her vision of the magazine. She took the responsibility of [Herizons] being a national voice for the women’s movement seriously.”

Nelle Oosterom is a writer and editor based in Winnipeg on Treaty 1 territory. She has written for Herizons and also served as a volunteer copy editor in the early 1990s.