On Sept. 13, 2022, Jina (Mahsa) Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman was arrested by Iran’s feared morality police for showing too much of her hair. She died three days later after falling into a coma from head injuries sustained while in custody. The public outcry over her death has fueled the most unprecedented show of dissent in Iran’s history. These protests differ from those in the past in scale and purpose, in that they are calling for the total abolishment—rather than reforming—of a theocratic government. Those at the forefront are young women, protesting the gender apartheid laws that led to Amini’s death with both real and symbolic acts of defiance.

Amini’s body defied death as the shaky Kurdish handwriting on her gravestone predicts.

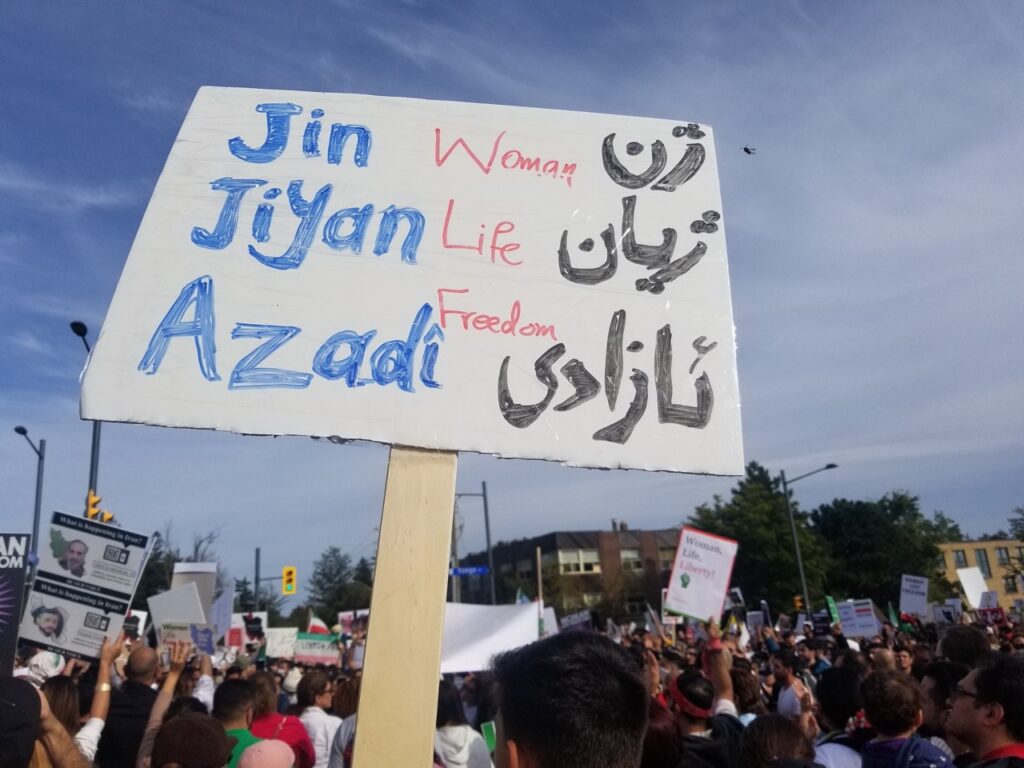

The movement’s revolutionary manifesto is the Kurdish slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî,” which swiftly spread from Amini’s home province of Kurdistan to the rest of the country—chanted in Kurdish or its Farsi translation, Zan, Zendegi, Azadi—meaning “Women, Life, Freedom.” Rooted in the 40 years of Kurdish women’s struggles against Turkey and ISIS extremism in Iraq and Syria, the slogan aspires to free all of society through women’s liberation. In her Toronto Star article published in Oct., Ava Homa writes “it’s not the first time that Kurds rise up against the Islamic Republic. They’ve opposed it since the beginning. But it’s the first time the rest of Iran has supported them.” Indeed, the slogan has guided protestors to mobilize the widening spectrum of marginalized groups against a repressive regime. As Angela Davis reminds us in a short video on @maliherazazan’s Twitter on Oct. 3, “when the protesters chant ‘Women, Life, Freedom,’ they are acknowledging the fact that when women rise up, they rise up on behalf of all people, all genders, queer and straight alike.”

The Women, Life, Freedom movement celebrates the body as the breathing, living foundation of being. “Life” and “Freedom” are the two fundamental conditions of existence that conflict with an imposed theocracy. The slogan does not give allegiance to narrow ideologies to motivate political action. It honours the individual as opposed to the collective, hegemonized and controlled, for the sustenance of the ruling system. No longer is the body bound in a socio-religious political cage, simplified and co-opted for a nationalist movement. Just as Iranians once willingly died as martyrs for “Vatan,” or the homeland, now they risk their lives fighting for the sovereignty of the individual and the right to self-determination.

“This is the uprising of the body, the natural body, the moving body, the rightful body, for only by returning to the body can we discuss life itself—as well as its miracles – Arash Heydari

In praise and defense of the Women, Life, Freedom movement, professor Arash Heydari eloquently offers a sociologist’s perspective in a viral video posted on @hammihanonline’s Instagram on Oct. 27: “this uprising has nothing to do with perversion but life itself,” he says. “This is the uprising of the body, the natural body, the moving body, the rightful body, for only by returning to the body can we discuss life itself—as well as its miracles…It is the body that sings. It is the body that eats. It is the body that drinks. It is the body that dances. It is the body that resists. It is the body that shouts.” Heydari alludes to all the ways by which the body can shake an oppressive system. He continues, “If we look at other social movements, we can find examples whereby the spirit has dominated the flesh. But this uprising is concerned with the flesh, not in the way they use the word to deprave it but in a broader sense that connects the word to life. For the earth is also a type of body.”

During the protests that have shaken Iran for over two months, women dance to the rhythmic chants of jubilant crowds around bonfires made from their mandatory hijabs. Their unveiled hair provokes, disrupts, and offends. Their bodies bravely resist and fight back when challenged. They raise their fists, wave their headscarves in the air, and stomp their feet. In grief and grievance, they cut off locks of their hair and with them, the hands of their oppressors. Others kneel before the regime’s gunmen and shout, “shoot me!” In classrooms, schoolgirls flip their middle fingers at the portrait of clerical leaders. The symbolism of bodily fluids, like blood, is used to desecrate imposed sanctity. Authorities have labelled them as “foreigners” or “agents of the enemy,” seeking to destabilize the country. Their defiant bodies are framed as heterodox; their uprising slandered as “the Revolution of the Whores.” But these women know that their individual acts of rebellion are a direct threat to the forced order of the Supreme Leader’s militant regime, currently under the control of Ali Khamenei, who holds sway over the military, foreign policy, state-run media, the judiciary, and key government organizations.

In addition to outright displays of defiance at demonstrations, sit-ins, and walkouts, the body’s subtle gestures have also helped catalyze the uprising. Perhaps a hug was the first gesture associated with the movement, when Iranian journalist Niloofar Hamedi took a photo of Amini’s parents holding each other in a Tehran hospital where Amini was lying in a coma. Hamedi remains in solitary confinement, potentially facing the death penalty. Her courage to break Amini’s story, however, has since been multiplied in the thousands who have risked being violently arrested or even losing their lives to protest Amini’s murder. Videos of protestors offering free hugs to embrace a sorrowful nation and boost solidarity continue. In this way, the hug has become a defiant act, not only breaking rigid gendered boundaries, but also weakening a government that has attempted to distance its citizens from one another in order to stay in power.

The emancipated bodies refuse to be quiet.

The sudden shock of fists pounding doors has long been associated with the regime raiding homes to abduct dissidents. This act was recently reclaimed in a video of Bahieh Namjoo (mother of Navid Afkari), whose son was detained in 2018 for protesting and later executed despite a global outcry. Namjoo is recorded pounding on a detention center’s gate, where, this time, her daughter Elham is held: “I will tear this door down!,” she says in Farsi. “Release my daughter or kill me!” The sound of her fists are in rhythm with the shouts of “Death to the dictator” from rooftops, cars honking, and the stomping feet of protesters.

The emancipated bodies refuse to be quiet and yet sometimes speaking truth to power can be heard more loudly through silence, as demonstrated by Iranian athletes refusing to sing the national anthem or celebrate their victories. Saeed Piramoon, professional Iranian beach soccer player, dedicated his goal at the Dubai Intercontinental Cup in early November to Iranian women when after scoring, he mimed cutting off his hair. Beyond the motivation for gold medals, protesting athletes display strength, endurance, and sometimes their hair—like Iranian sport climber Elnaz Rekabi, who competed without a mandatory headscarf in an international contest. In the face of devastating pressure outside of their games, athletes have been risking their lives to show support, without raising their voices.

What began as a protest over one woman’s murder has grown into a national movement with global support against the oppression and brutality that led to her death. Amini’s body defied death as the shaky Kurdish handwriting on her gravestone predicts: it translates, “Jina dear, you won’t die. Your name will become a code.” Social media has played a huge role in giving the movement traction, as the hashtag #mahsaamini has been shared millions of times, becoming the “code” her epitaph foretold. The defiance of bodies continues despite the regime’s intensifying crackdown, with at least 18,000 arrested and hundreds killed—disproportionately involving ethnic/religious minorities, like the Kurds and the Baluch. Our valiant martyrs continue to dance in video and image, forever remembered, joyful and free. They died wanting nothing more than to live.

Dancing in protest, some will fall—but together we rise.

We rise.

We rise.

We rise.

A Reading List

To help contextualize the protests in Iran and the Women, Life, Freedom movement, we hope this list will spark conversations and keep us connected, educated, and moving forward.

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

Zahra’s Paradise by Amir & Khalil

Kurdish Women’s Stories edited by Houzan Mahmoud

This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States by Manijeh Moradian

Children of the Jacaranda Tree by Sahar Delijani

Enghelab Street, Iran 1979-1983: A Revolution through Books by Hannah Darabi

The Other Side of Silence: A Memoir of Exile, Iran, and the Global Women’s Movement by Mahnaz Afkhami

Disoriental by Négar Djavadi

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar

Sara: Prison Memoir of a Kurdish Revolutionary by Sakine Cansiz

Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers by Farzaneh Milani

Soundtrack of the Revolution: The Politics of Music in Iran by Nahid Siamdoust

Sexual Politics in Modern Iran by Janet Afary

Conceiving Citizens: Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran by Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet

Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity by Afsaneh Najmabadi

Assassins of the Turquoise Palace by Roya Hakakian

The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and the Politics of Dislocation by Reza Zia-Ebrahimi

Days of Blood, Days of Fire by Bahman Jalali

Daughters of Smoke and Fire by Ava Homa

The Daughters of Kobani by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon

Women and Politics In Iran: Veiling, Unveiling and Reveiling by Hamideh Sadeghi

Falgoush is an experimental publishing and curatorial project that explores Iranian narratives of identity and belonging . Borrowing its name from a New Year’s Eve ritual of divinatory eavesdropping, Falgoush seeks unconventional cultural modes of expression to dispel the darkness of remaining unheard and unseen, while building collectively into a space of cultural exchange and community. Learn more at falgoush.com.