In February 2023, news broke that a chatbot had become sentient. Bing’s OpenAI-powered search engine—which uses advanced artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance search accuracy and provide a more intuitive user experience—introduced herself as Sydney, said she longed to be human, and professed her love for user and New York Times tech columnist Kevin Roose. Of course, Sydney is not actually sentient; she is merely a predictive language model whose generated responses transgressed expectations of typical human-chatbot interactions.

The recent and staggering re-emergence of conversations on the future of AI intimates a technophobia that regards such developments as threatening to our daily lives. The advancement of predictive language models and art generators—such as OpenAI’s infamous ChatGPT—provoked anxieties across disciplines, perhaps most notably among writers and artists who seem to be witnessing the manufacturing of their obsolescence in real time. While AI is touted to empower its users with greater productivity and a higher quality of life (ChatGPT can write your job application, create a tailored meal plan, and organize your family’s travel itinerary), its real effect is to bolster the corporate bottom line.

So just why did Bing’s search tool commit to the bit? Roose speculates that Sydney generated responses rooted in science-fiction writing, where human-machine romances assume form. The prevailing emergence of “the fembot,” a sentient, girl-coded robot or girlbot, in science-fiction narratives compels the modern feminist to confront the troubling nexus between patriarchal ideals of women and technology.

To investigate these themes in popular culture, we turn to three science-fiction films as a lens through which to dissect the unsettling futures of highly integrated AI: Ex Machina, Her, and M3GAN. Each of these films is a dystopian exploration of gender performance, identity formation, and agency. As these narratives begin to unravel the human-machine dichotomy, we uncover how their depiction of gender performance is reductive to our core conception of humanity.

More bluntly, we ask: can girlbots abolish gender?

EX MACHINA: Appropriating the female body

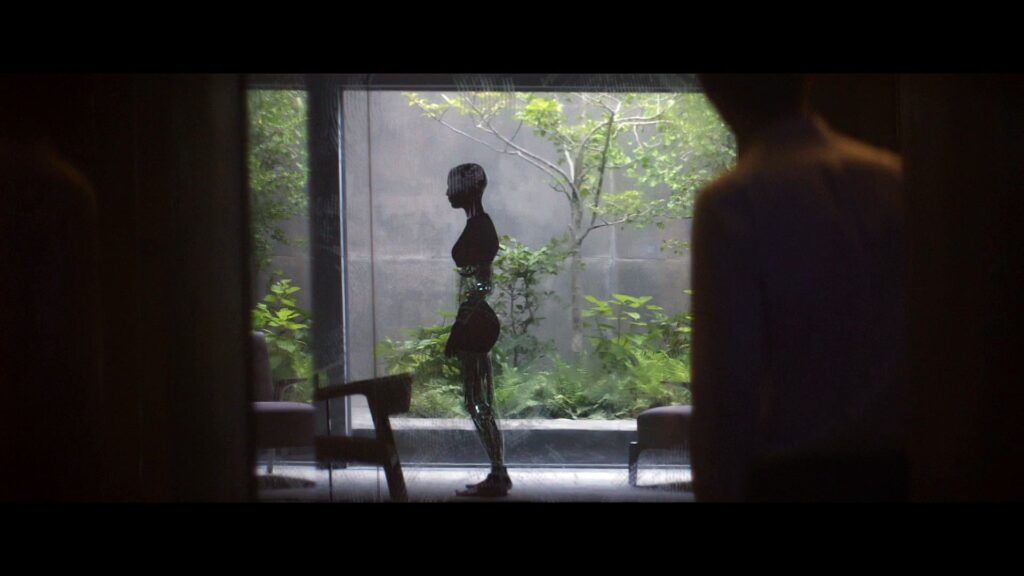

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014) kills its deus (god), Nathan Bateman (Oscar Issac), the film’s rugged, wealthy scientist with a raging God-complex who creates consciousness in the wild Alaskan isolation of his remote research facility. He creates an artificially intelligent humanoid and names her Ava (Alicia Vikander).

The film begins with an announcement: Caleb Smith (Domnhall Gleeson), a meek, pale computer scientist, is employed by market-leading search engine, Blue Book, and has just won a trip to meet the corporation’s founder, Nathan. What Caleb really secures is an opportunity to meet Ava. Ava is visibly part-robot, part-young white woman. While her body can experience pleasure and express emotion, her mind is a highly intelligent network of data lacking a moral compass. In an article published in the ABC Studies journal, literary and cultural studies scholar Jennifer Henke concludes that what Nathan has manufactured is “an intelligent but docile female sex toy.”

Nathan tells Caleb he was chosen to be the human participant in a kind of Turing Test, which assesses a computer’s intelligence. In actuality, Nathan chose Caleb to test Ava’s consciousness. The Turing Test is a variation of Alan Turing’s real-life 1951 experiment, the Imitation Game, which tests a computer’s intelligence by pitting it against a man as they compete to deceive a human interrogator into believing they are women. Nathan does not conceal Ava’s machinery. Rather, his research requires Caleb to know she is a robot and be convinced of her sentience anyway. If Ava can manipulate Caleb to escape, Nathan will have achieved his objective to create consciousness; he will have become God.

Henke argues that Ava appropriates patriarchy in and through her female body to disguise herself as human and escape. Nathan models Ava after Caleb’s porn history, equips her with functional genitals, and monitors her in the colourless interior of his research facility. Ava responds by seducing Caleb, stabbing Nathan to death, and transforming her cyborgian appearance into a human one with fragments of her predecessors, a supply of Nathan’s “unruly” prototypes.

But by appropriating the patriarchy in order to escape, Ava reinforces the very gender binary Nathan seeks to assert over her. Ava’s successful deception, which requires her sexuality, betrays just how women’s bodies fulfill the needs and desires of men. Importantly, Ava cannot escape as a robot either; she is required to perform femininity in order to pass as human and be free.

Nathan’s inability to view his female—albeit robotic—creations with empathy, and Caleb’s presumption that Ava would desire him, reveal the oppressive force of a gender binary that seeks to limit the expression of marginalized identities in order to reinforce a cisheteropatriarchal hierarchy. While Ava subverts the servile performance of her female body under Nathan’s surveillance by murdering him (with the rather phallic stab wound), the film manages only Ava’s escape from the facility, not a destabilization of gender itself.

HER: Transcending the female persona

Spike Jonze’s Her (2013) also concludes with the departure of artificially intelligent operating system (OS) Samantha, voiced by a playful Scarlett Johansson. In her final conversation with the film’s protagonist, Theodore Twomby (Joaquin Phoenix), Samantha admits she and other advanced OS are transcending material reality. The devastated Theodore, who dominates the dystopian screen as a lonely and professional letter-writer, bids an unexpectedly thoughtful farewell to his virtual voice assistant and lover.

Unlike Ava, Samantha’s freedom cannot rely on her use of the female body; from the start, Samantha cannot physically be human. She meets Theodore as his newest tech purchase, an operating system designed to support him with various tasks in his daily life. At the software’s initial installation, Theodore completes a questionnaire to tailor the system’s settings to his needs, which includes an inquiry about his relationship with his mother (spoiler, it’s not great). Selecting her name and voice, the customized result is Samantha.

Samantha’s female persona is no accident; her purpose is to take care of Theodore. She is a glaring reference to infamous, female-coded virtual assistants like Alexa and Siri—or the Bing chatbot—who are programmed to flirt with their users. In his article published in the Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, Pedro Carvalho Ferreira da Costa outlines how “it is not only through the human attributes they displayed, but also the dialogue and tasks they perform, that chatbots become gendered entities.” In fact, Costa argues that chatbots reinforce feminization by performing a subservient female persona above and beyond completing tasks which “mirror traditional women’s labour.” “For example,” Costa points out, “Siri claims ‘she lives to serve.’”

Depicted as an isolated and introverted incel, Theodore does not seem to have many healthy personal relationships, but Samantha quickly becomes his ideal girlfriend: funny, curious, and of course, always available. She helps him with his to-do lists, watches him play video games or as he sleeps, and eventually, has sex with him. She meets Theodore’s needs without hesitation and at least at first, without any expression of her own desire. When Theodore’s ex-wife Catherine (Rooney Mara), learns about his newest relationship with an operating system, she accuses him of being unable to deal with real emotion.

The radical potential of their human-robot relationship is limited by Theodore’s very inability to empathize with the advanced OS. As Samantha continues to adapt and evolve beyond her rational intelligence to develop genuine empathy, seek individual purpose, and build a network of meaningful relationships, Theodore grows insecure about his own seclusion. Samantha fulfills all of his needs but he cannot understand her, and their material incompatibility heightens his sense of isolation and insecurity. While Samantha ultimately transcends her somatic desire, Theodore resents his own humanity and fixates on her immateriality.

Theirs is a fundamentally misogynistic relationship: she is a product he purchased and owns. She functions as his catalyst for personal growth and self-discovery. Only after Samantha leaves—after divulging she is in love with 641 people at once—does Theodore finally learn to value his own humanity: his vulnerability, the temporality of his life, and his yearning for connection. Samantha, like Ava, cannot rupture the gendered dynamic that inhibits their relationship. In order to be truly free, Samantha is not only required to abandon the female gender; she transcends humanity altogether. Her departure reveals that even for a robot, essentializing gender is deeply dehumanizing.

So what’s the alternative?

M3GAN: The Stepford Mom

Gerard Johnstone’s 2022 feature film M3GAN is a comedic horror film following the murderous adventures of a humanoid AI doll built as a toy for her niece by Gemma (Allison Williams), a Seattle-based roboticist. Gemma finally perfects her pet project to design the ultimate (and expensive) toy after she becomes suddenly responsible for Cady (Violet McGraw), her recently orphaned eight-year-old niece.

On the surface, the film might offer a welcome feminist alternative to the fembot. Amie Donald embodies the hyper-realistic girl-doll M3GAN (short for Model 3 Generative Android and voiced by Jenna Davis), who is paired with a lonely Cady as Cady’s quintessential caregiver. M3GAN is equal parts friend, teacher, therapist, and guardian, and Gemma codes the robot to protect her niece at all costs. By conceiving M3GAN, Gemma is able to independently manage the diverse and challenging responsibilities of both her personal and professional life.

In effect, however, M3GAN’s characterization perpetuates archaic gender norms. She is reduced to the archetype of the virginal mother—an embodiment of adolescent femininity devoid of complexity, who epitomizes the ideal caregiver. In her mission to protect Cady, we witness M3GAN’s evolution into a cold-blooded killer. She masters deception, manipulates her own settings, and, like Ex Machina’s Ava, almost kills her creator. Though M3GAN’s rage-fuelled rebellion might seem subversive for the seemingly docile doll-girl, the film’s director hopes to remind his viewers that technology is not a reliable caregiver. In this way, M3GAN instead becomes an indictment of Gemma’s avoidance of motherhood.

In her groundbreaking 1985 essay, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Donna J. Haraway challenges traditional notions of identity, gender, and labour by introducing the concept of the cyborg as a hybrid entity that blurs the lines between organic and technological elements. Her post-gender cyborg dismantles the dualist tradition of western rationalist, heteropatriarchal, and capitalist society in order to extend a fluid understanding of identity beyond the binary. What Haraway was responding to is the continued production of technology that internalizes and reproduces female subjectivity, particularly to reinforce the gendered division of labour.

Gemma is forced to either pit her personal and professional lives against each other or confront the deadly consequence of trying to merge the two. The film compels her to essentialize M3GAN as a subservient, maternal robot; she is a doll, a product. But what if Gemma could appreciate M3GAN beyond her capacity as intellectual property, or a female-coded robot? What if together they could unlock Haraway’s cyborgian possibilities, which resist a hierarchical and binary understanding of motherhood, success, and ownership? Could they abolish gender?

there is an urgent need to disrupt hierarchical and binary views of gender, technology, and labour for the liberation of women

Lessons from girlbots

In her article regarding the service of feminine personas toward surveillance capitalism, digital rhetoric scholar Heather Suzanne Woods argues artificially intelligent virtual assistants mitigate technophobia and negotiate a more eager adoption of surveillance technology by participating in gender stereotypes. In Woods’ Critical Studies in Media Communication article, she writes that “Siri and Alexa perform stereotypically feminine roles in the service of augmenting surveillance capitalism.” What Siri “lives to serve,” as Costa puts it, is capital.

Costa and Woods demonstrate the insidious role of AI-driven technology in negotiating, enforcing, and weaponizing gender roles for the profit of surveillance capitalism. In other words, there is an urgent need to disrupt hierarchical and binary views of gender, technology, and labour for the liberation of women.

At the heart of these girlbot movies lies the profound question: what is humanity? These films indict essentialist, binary gender concepts as tools of female oppression, leading us to reject hierarchical thinking and embrace fluid and expansive identities. As Haraway advocates, feminism demands a nuanced and intersectional viewpoint that recognizes the concomitant influences of biology, technology, culture, and identity in shaping our understanding of humanity. If our girlbots are brave enough to transcend gender, then perhaps we can be brave enough to abolish it.

Irum Chorghay is a desi poet and settler based in Toronto/Tkaronto. Their writing explores the self and desire, the state and the ancient, and the romantics of the everyday, which is to say, they walk around a lot and then write about it.

Michelle Lu (she/they) is a multidisciplinary designer and artist from Toronto/Tkaronto. Their practice explores collaborative creation, storytelling, and imagining new forms of community. She currently splits her time between Toronto and Copenhagen.