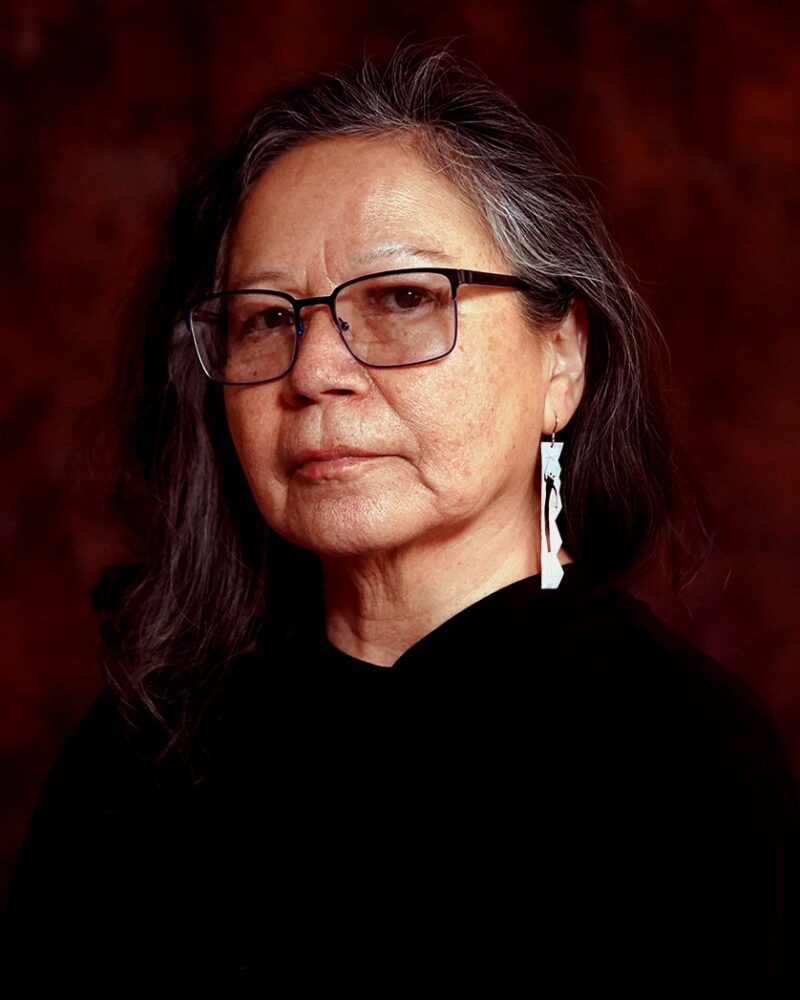

With a career spanning four decades, Shelley Niro, 70, is one of the most prominent and prolific Indigenous artists in Canada. Born in Niagara Falls, New York, and now based in Brantford, Ontario, Niro is a member of the Turtle Clan of the Kanyen’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation, Bay of Quinte Mohawk, and Six Nations of the Grand River.

Niro explores the world around her in intimate detail through photography, film, video, painting, printmaking, beadwork, and mixed media. Her artistic practice reflects on family life on the rez (reserve), the cosmos, and everything in between. Her oeuvre visualizes Haudenosaunee worldviews, connections to place (land and waters), the impacts of colonialism, problematic and persisting stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples—especially women—and matriarchal bonds. Wit, irony, and satire are critical instruments in her artistic toolkit. Niro’s work is as accessible and resonant as it is aesthetically beautiful and conceptually rich; it’s humour with heart.

Niro’s work is as accessible and resonant as it is aesthetically beautiful and conceptually rich; it’s humour with heart.

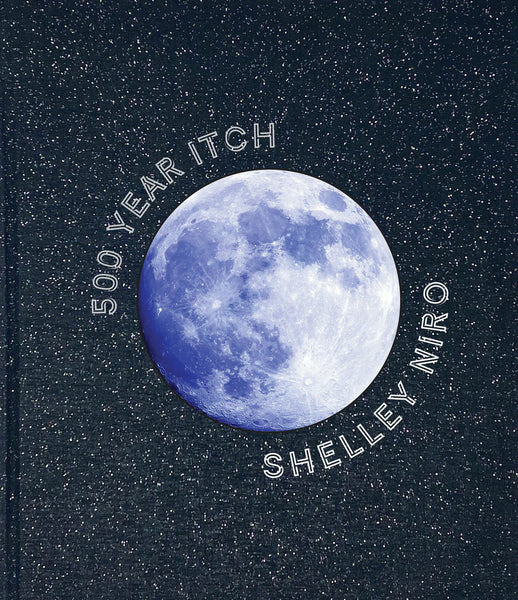

I sat down with the artist at the Art Gallery of Hamilton (AGH) in mid-April to talk about her art practice and the process of creating her first major solo retrospective exhibition, Shelley Niro: 500 Year Itch. Over seven years in the making, it features more than 70 of Niro’s works, some in series, totaling 136 pieces. A beautifully designed and heavily illustrated 304-page publication of the same name was also released alongside the exhibition. It features Grandmother Moon on the cover—a protector and guardian of Turtle Island in Haudenosaunee culture—reflecting Niro’s curiosities about our place in the universe.

500 Year Itch is currently on view at the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa) until August 25, and will travel to the Vancouver Art Gallery in the fall and Remai Modern (Saskatoon) in the spring.

Rhéanne Chartrand: Thinking back to your childhood on the rez, what did you aspire to be? Were you always a creative being? When did you start beading, painting, and photographing?

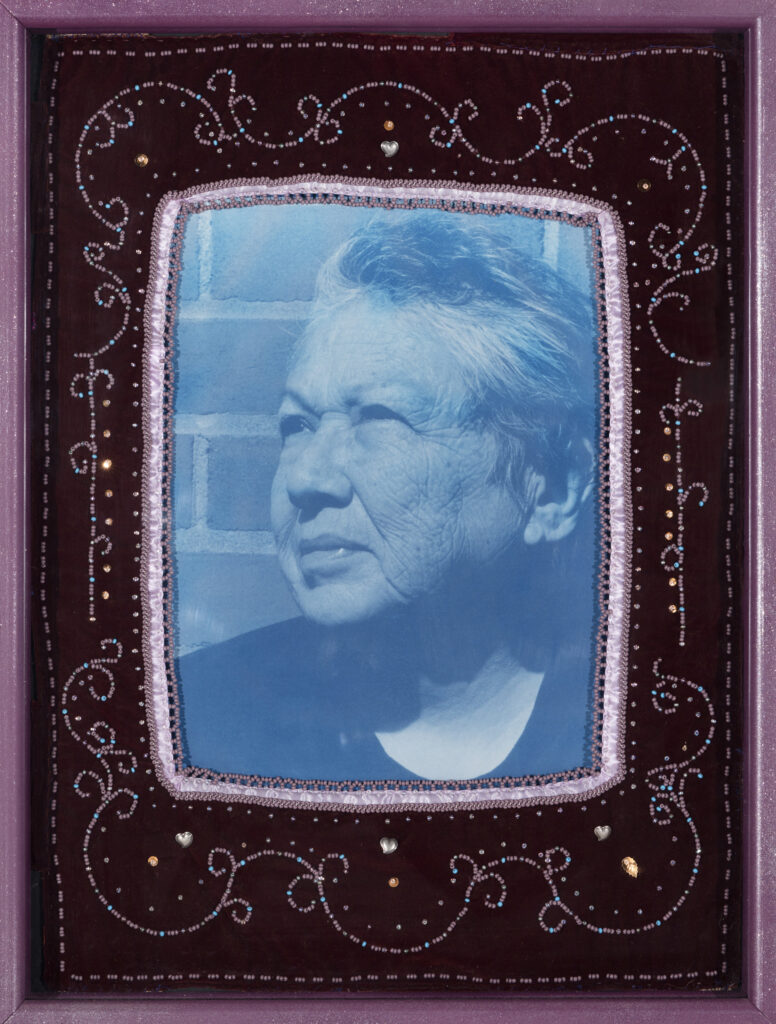

Shelley Niro: Yes, I think so. But I never said to myself, “I’m going to be an artist.” I think myself and everyone around me were living that life anyways— people were always singing, dancing, and making despite being a poor, poverty-stricken community. Everyone had beads in their house; it was the ubiquitous art material that everyone could afford. I remember getting little vials of white beads and having needles. It was something we all had, and it was largely self-taught. Beading is a good way to start off because you learn your fine motor skills and patience. I believe beading should be a part of everyone’s art practice. It’s good for your brain.

R: Where does the title, 500 Year Itch, come from? How does it feel to be celebrated as one of the most important senior Indigenous artists on Turtle Island?

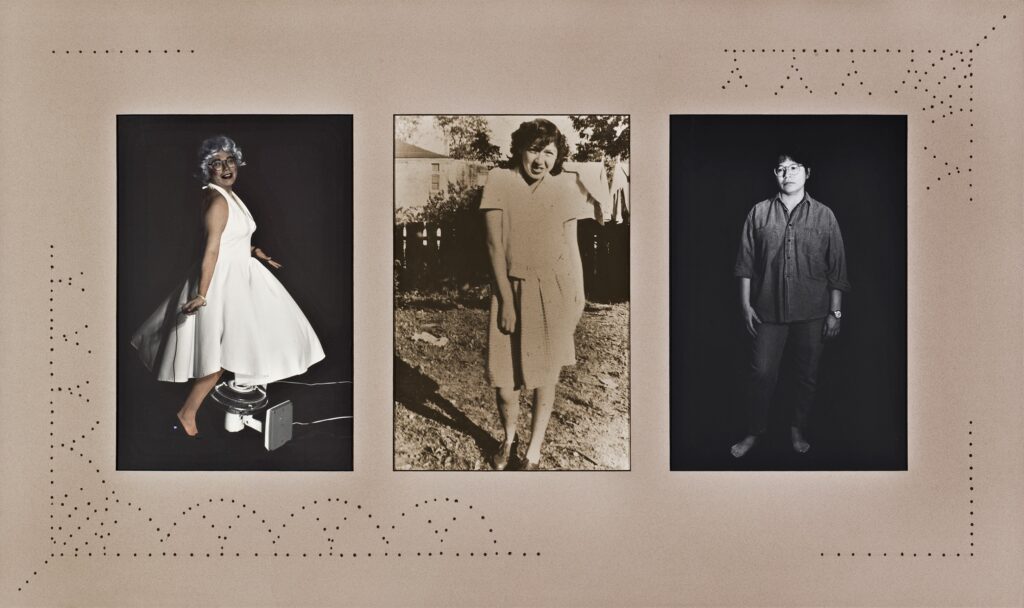

S: I’m humbled and honoured. I’m inspired by Yayoi Kusama, who is 95-years-old, and I think to myself, “If she can do it, I can do it too.” And so I keep on going. The title is inspired by a photograph I created in 1992 of the same name. 1992 was the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus landing in the Americas, so that’s where the title of the piece, 500 Year Itch, originated. When you think about 500 years, and the 30 years since 1992, well, it’s a quick and easy way of remembering the time since colonization.

It’s also based on a film with Marilyn Monroe called The Seven Year Itch (1955), which focuses on a dysfunctional marriage, questioning, “Will the marriage last beyond the seven-year period?” Psychologically, people will ask, “Is the marriage good or bad?” So, using the title 500 Year Itch provokes the question, “Is this a relationship (Indigenous-settler relationship) that is going to last, or is it gonna fall apart?”

R: I was exposed to your photography and filmmaking early in my career, and it left a lasting impression on me. But just as my career has shifted and changed, so too have I witnessed your practice grow and evolve. Do you approach painting, installation, and beadwork in the same way as photography and filmmaking?

S: With photography, the idea has to formulate in my head before I can pick up a camera. It’s about working through how to make my idea material. Also, there’s a lot to think about when creating an image, technically-speaking. I love doing portrait photography and getting my family and friends to sit for me. They’re quite happy to participate, and we talk as I set up my equipment.

The older I’ve gotten, the less I’ve cared about being “good enough.” It’s about shedding the self-criticism; it’s self-destructive and doesn’t get you anywhere. I don’t have the time to waste on being down on myself.

I don’t think I’d like it as much if I didn’t know the person. Photography and filmmaking are a social type of art-making because you’re involved with so many people in the creation process. My first short film was It Starts with A Whisper (1993). I think people underestimate how emotional filmmaking really is; you have to be focused on what you’re trying to do while thinking of everybody on set. With my newest film, Café Daughter (2023), I had to be really sensitive to the emotional story we wanted to tell—a coming-of-age story about a young Chinese Cree girl in 1960s Saskatchewan who is told to keep her Cree identity a secret. It helped that the cast was superb and really committed to getting it right.

With beading and painting, you’re alone in your studio, you can put your music on, and the day just swishes by. It’s a totally different mental state—it’s more private. I’ve been painting longer than I’ve been doing photography, but I’ve thrown out paintings in the process of refining my skills. The older I’ve gotten, the less I’ve cared about being “good enough.” It’s about shedding the self-criticism; it’s self-destructive and doesn’t get you anywhere. I don’t have the time to waste on being down on myself.

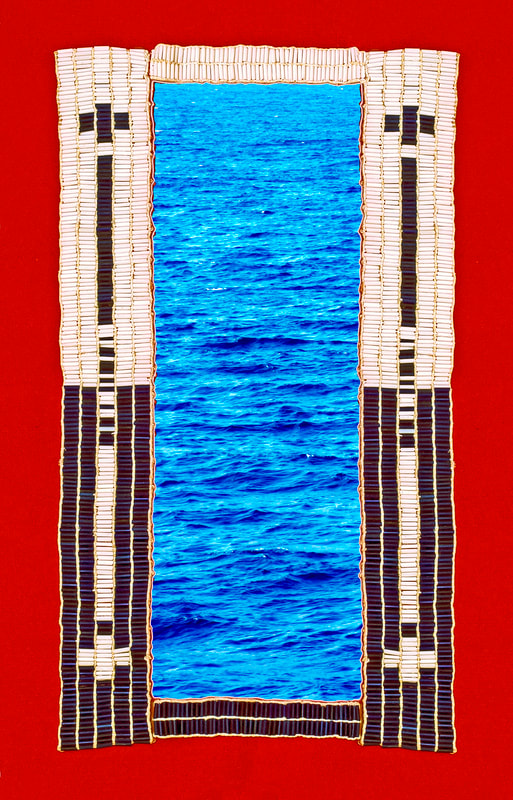

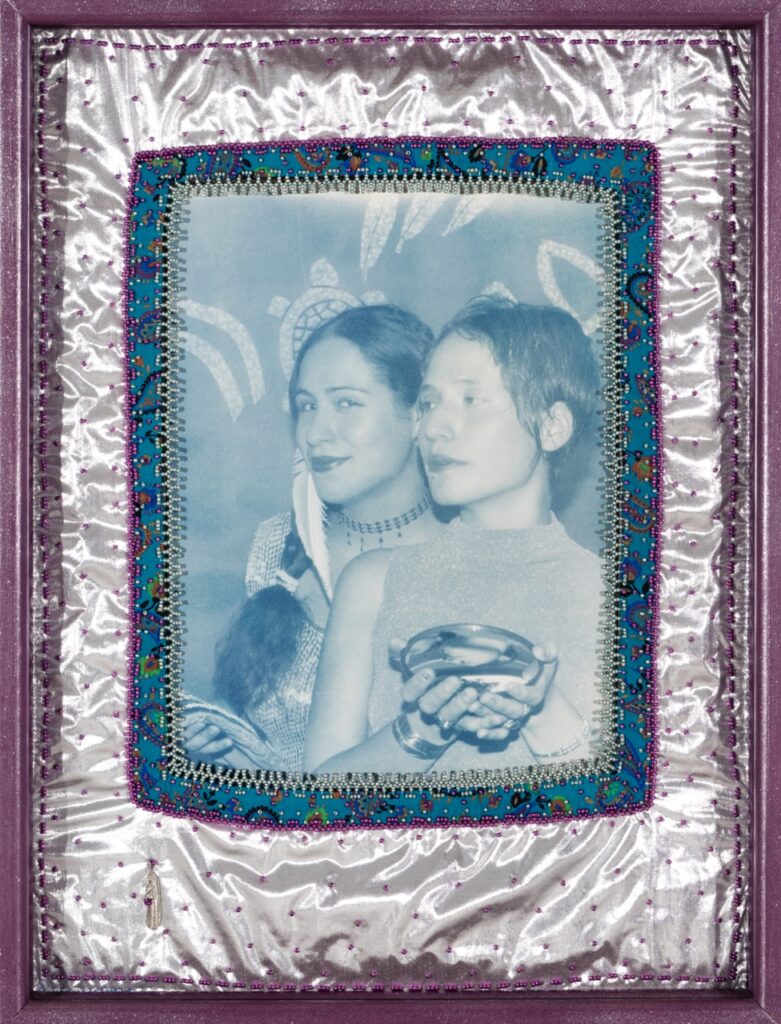

R: The Shirt is one of your most iconic works of art. Notably, it was presented at the 2003 Venice Biennale. Can you walk me through what led you to create the series? Was there a particular catalyst or issue you wished to redress? And what was it like collaborating with the actors (Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie and Veronica Passalacqua), whom I understand to be good friends of yours?

S: In 2002, I was on a flight to Houston, Texas to attend a photo conference taking place there, and I looked out the window and noticed that the land there is cut up into perfect squares. It looked like a quilt. Then I started thinking about the Comanches who fought hard for their land, and who were condemned—much like the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)—as bloodthirsty for trying to keep hold of their land. And sadly, they didn’t succeed.

Upon display, someone made a comment that the word “annihilated” was spelled wrong on one of the shirts and suggested I fix it. I thought to myself, “English isn’t our language,” and the mistake reminds me of that fact.

The words for The Shirt started to come to me. I got to the conference and asked Hulleah and Veronica to participate in this idea I had and they agreed. A year later, I went to Irvine, California, where they were living, with the shirts and the text. We did the photo and video work at the same time, shooting in a state park in California, because I wanted to have the Pacific Ocean on one side of the video and end with the Atlantic Ocean on the other side of it. While shooting, a park ranger approached us and said over a microphone, “Put down your camera and step away.” We were so confused at first and then we realized he was talking to us. Unfortunately, it was at the part when Hulleah was topless! He said that while we were allowed to take pictures there, only “family cameras” were al- lowed, and indicated he’d confiscate my equipment or fine me $5,000 USD if we didn’t stop. So, we just packed up and left.

In the final video, I included shots of Niagara Falls, to connote the power of water, but sadly, the shots I wanted of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans never happened because of the ranger. In 2004, The Shirt (lightbox edition) was presented at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York. Upon display, someone made a comment that the word “annihilated” was spelled wrong on one of the shirts and suggested I fix it. I thought to myself, “English isn’t our language,” and the mistake reminds me of that fact. I still have the shirts.

R: You portray Indigenous women in a wholistic way, allowing them to be their full selves. Your depictions reveal us to be resilient, powerful, vulnerable, tender, and sassy. At what point in your long career did you decide to make Indigenous women a central subject of your practice? As a Kanyen’kehà:ka woman, how have your cultural values influenced how you depict women? And what would your Mom, Chiquita, think of becoming an icon through your work?

S: I realized in looking at images out there of Indigenous women that the representations of us were limiting. They made Indigenous women look like they didn’t have a thought in their head, like they were two-dimensional. I felt like the layers of personality and character weren’t there. Looking at the women in my family, and women in general, we’re always laughing and entertaining each other.

Looking at the women in my family, and women in general, we’re always laughing and entertaining each other.

Waitress (1987) was one of the first works where I directly confronted [mis]representations of Indigenous women, and I used myself in that painting. During the prime ministership of Brian Mulroney, there were many news articles being written about “Indians” being welfare people, taking from the government and taxpayers, almost being looked at as a disease on society. I thought to myself, “We’re working our butts off to live!” To have that kind of characterization— putting us in a position to be hated by using us as a scapegoat for federal financial mismanagement—I depicted myself as a waitress to show how hard we work. My mom and dad were always working; my mom always had these horrible jobs as a housekeeper and cleaning at the YMCA. I would think to myself: “People have the wrong idea about Indian People.”

My mom was so happy to be involved in any of the work I’d be making. She was a happy participant and that helped me because it made for a great experience creating work. She’d love the fact that she’s on a T-shirt!

R: A continuous thread in your work is your relationship to the cosmos, specifically the Grandmother Moon that is beautifully depicted in a lightbox. What draws you to the night sky and exploring Haudenosaunee cosmologies, both thematically and aesthetically, in your work?

S: I think it comes back to growing up on the reserve and being totally enveloped in that sky at night, which I probably didn’t appreciate at the time, but I was drawn to it anyway. Having left the reserve and now living in the city, you don’t see the sky that you once could see before light pollution. I find I really miss having those stars above me, and it’s something that I’m really drawn to and want to photograph and keep memories of. I have recurring representations of the moon in my work. The universe is so vast and infinite and it goes on and on and on. I just like to think that’s how our imaginations can work too—that there’s no limit to what we can imagine or create or do. Go outside and look at the sky; it’s limitless.

Rhéanne Chartrand (Métis) is a curator at the Royal Ontario Museum and the 25th edition of Art Toronto. She holds a master’s degree in museum studies from the University of Toronto.